Pensions: Solving the perception puzzle

June 21, 2021 • 15 minute read

Introduction

Pensions have a PR problem. Complexity, inaccessibility, lack of transparency and regular scandals have over time created a major trust issue that adversely impacts attitudes towards saving for retirement.

The result is that many people are almost completely disengaged with and unprepared for probably the most important financial factor affecting later life. A variety of complex, interconnected issues and challenges lie behind what is driving this trust issue, for which better understanding and communication are critical for pensions market players, policy makers and pundits alike.

To better understand this problem, and how it can be addressed, Infinite Global partnered with research group YouGov to examine public attitudes towards pensions. We also analysed how the issue is portrayed in the mainstream media and spoke to key figures from the world of pensions, including senior financial journalists from The Times and Financial Times, to unpack this trust issue and establish where the ‘burden’ of trust-building lies.

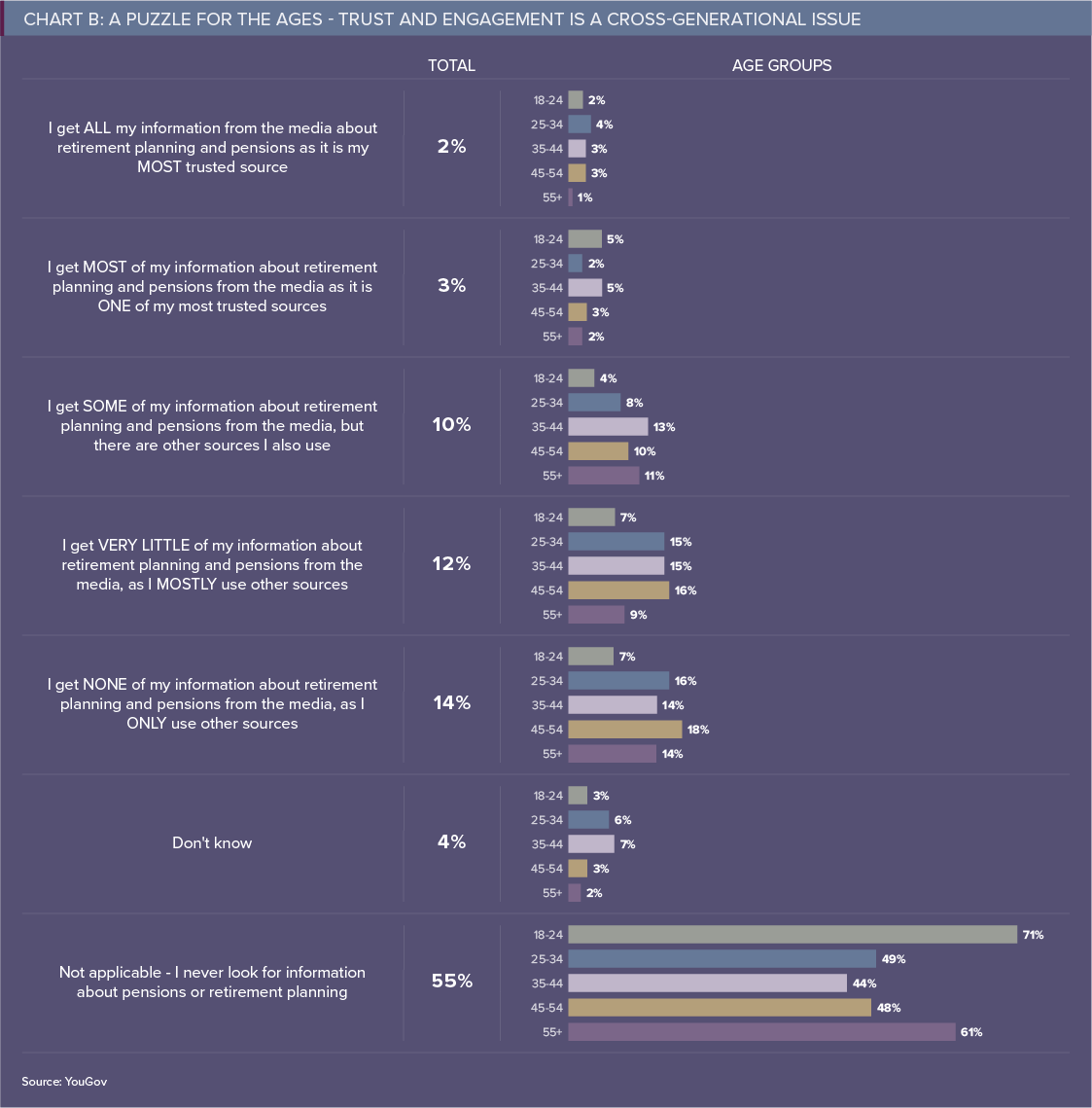

By gauging public opinion our research found a clear lack of engagement on pensions. Across all age groups and demographics, people remain uninterested in and apathetic towards the subject, with more than half (55%) of Britons noting that they do not look for pensions information from any source.

This was even more pronounced among 18-24 year-olds, where the proportion of people not looking for information about pensions at all reaches almost three-quarters (71%), and is even higher (83%) for those in full-time education (See Chart B).

Part of the trust and engagement problem seems to stem from not knowing where to look. A quarter of Brits (26%) get none, or very little, of their information about pensions from the media, instead favouring other sources. This compares with 15% who say they get all, most or some of their information about pensions from the media as a trusted source.

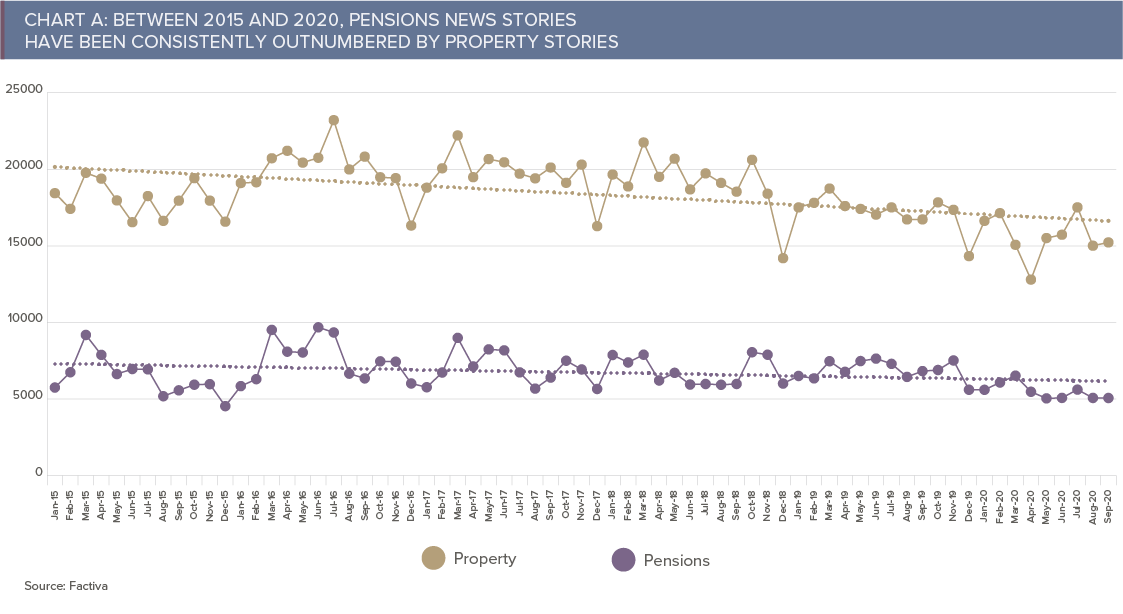

Supplementing those findings, Infinite Global conducted analysis of news reporting around pensions to establish why people feel uncomfortable in consulting the media. Our media analysis found a steady and consistent, though not drastic, decline in the volume of mainstream media coverage of pensions issues over the past 10 years.

It also revealed a tendency to focus on ‘negative’ news, sometimes driven by scandal or by the prospect of pension poverty. For anyone who understands what drives the news agenda, this is to be expected. Nonetheless, it may still represent a root cause of disengagement and mistrust.

Further analysis of personal finance reporting more broadly identified another contributary factor to pensions apathy – namely a lack of cut-through, evidenced by a ‘weaker’ media footprint for pensions when compared with other personal finance issues, particularly property. We’ll look into the implications of our research in more detail below, but suffice to say at this stage they show that pensions – not unlike many other aspects of personal finance – is an area that is at best misunderstood and, at worst, mistrusted.

This is important because most people are not saving enough for their retirement. Pension provision in the UK is still among the lowest across OECD countries and the scale of the problem should not be underestimated. A recent survey found that two-thirds of adults retiring this year risk running out of money while only 39% of them felt very confident that they are financially ready to do so – with women slightly less confident than men.

Yet apathy and inertia rule. This poses significant challenges, not just for individuals but for all stakeholders, and especially for communicators.

Research Highlights

Our survey of public attitudes to pensions – carried out in conjunction with YouGov – found a clear lack of trust and engagement on the issue across the board. This is also reflected in media coverage of pensions compared with other personal finance and savings issues such as property, which attracts more interest and coverage even though more wealth is tied up in pensions.

Pensions: Perceptions and Realities

Public versus private sector

Pensions are an issue for everyone, but the landscape is far from level. For example, about 6.6 million public sector workers have defined benefit (DB) pensions, which offer a ‘gold-plated’ guaranteed, inflation-linked income for life based on their final salary or, increasingly, their career average.

These DB schemes typically pay an annual income of around £4,000 – for many that’s no more than a useful top-up to the state pension but at least it’s one that doesn’t carry any investment risk and gives some peace of mind.

Compare that with the private sector, where just over one million workers still have final salary pensions, down from 3.6 million in 2006. The vast majority of private sectors workers, if they have a pension at all, are in less generous defined contribution (DC) pension schemes, where retirement pay-outs depend on investment performance.

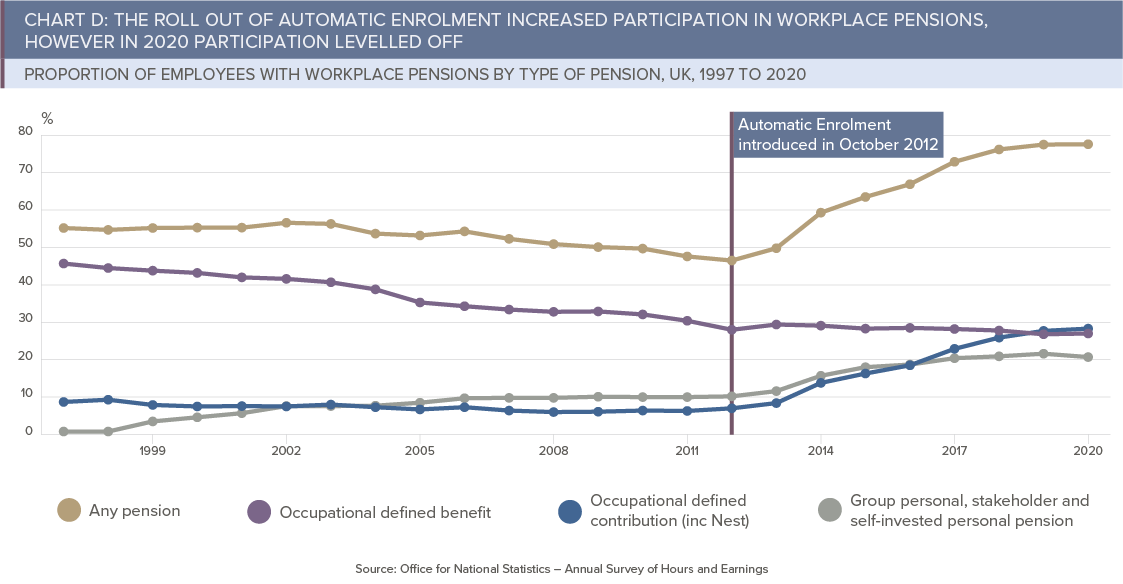

Auto-enrolment coupled with the introduction of pensions freedoms which allow the over-55s to take a tax-free lump sum from their pension pots has increased involvement. However, as our research and conversations with industry participants suggest – greater involvement does not necessarily mean more or better engagement. This is evidenced by the FCA and TPR’s May 2021 ‘Pensions Consumer Journey’ call for input document which notes that 99% of all savers in open DC membership schemes stay within the default fund. This struggle to engage, the paper notes, can mean consumers: fail to make decisions that optimise their pension saving; remain in poor performing products, often originally chosen by their employer; and are susceptible to scams.

Some nine million people are now auto-enrolled into DC schemes but a lack of communication with them could be storing up trouble for the future, especially as workers paying minimum contributions may walk unwittingly into unsatisfactory retirement outcomes without knowing it.

The risk is that people are lulled into a false sense of security by thinking ‘minimum’ is ‘enough’. “It’s a bit like the minimum payment on your credit card,” explains James Daley, cofounder and managing director of Fairer Finance. “You have the option to pay the minimum amount and you can fall into a trap of thinking that’s enough, but if you continually pay only the minimum amount, you’ll be paying it off forever. We haven’t seen that crisis come to fruition yet.”

Even where pension provision is good, it may not be enough. For example, a recent survey by actuarial firm Lane Clark and Peacock found that pensioners are facing a dramatic drop in income over the next two decades as fewer and fewer private sector workers reach retirement with the boost of a final salary pension.

Better communication is vital if the gap between pension provision expectation and reality is to be closed.

“A lot of people have ludicrously inflated expectations about return on their investment,” says Patrick Hosking, Financial Editor of The Times. “No wonder people are disappointed with pensions if they think they are a low-risk way of growing investments by a large amount.”

Property versus pensions

On one level the lack of engagement about pensions, and the relative decline we’ve seen in media coverage on the subject in recent years, is curious. After all, pensions are the nation’s biggest asset class, worth £6 trillion, compared to £5 trillion for property, according to ONS data on where wealth is concentrated.

In part, this oversight is because pensions are seen as less glamorous than other investment channels. “Whether it’s investing via ISAs or buy-to-let, other options are proving to be more attractive alternatives,” says Anthony Morrow, co-founder and chief executive of OpenMoney.

Our analysis found that property-related stories have outnumbered pensions-related ones by roughly three-to-one since 2015. Morrow puts the greater media attention that property commands down to the relative ease with which saving for a home is grasped: “The broadsheets regularly run articles around ‘property versus pensions’ and bricks-and-mortar represent a more tangible option for many whereas pensions have this almost Byzantine aura of complexity.”

Lindsay Cook, Money Mentor columnist at the Financial Times agrees, but warns that a pre-occupation with property should not come in place of, or at the expense of, pensions: “Too many people see their home or buy-to-let as a source of retirement income.”

“The situation hasn’t been helped by the number of people not entering the housing market until they are in their late 30s or early 40s,” she adds. The result is a lack of spare funds that would have been available from paying off a mortgage before they retire. Today, an increasing number of people are still paying mortgages when they retire and more over-50s are renting in the private sector.

Advice versus guidance

Our survey found more than half of us do not look for pensions information from any source.

Nowhere is this lack of engagement – and lack of trust – exemplified better than the advice gap.

Research from Open Money reveals the scale of the problem. Some 20.9 million UK adults who would potentially benefit from advice are unaware of free advice channels like the Government’s Money and Pensions Service, or are unable to access them. While 22% of people said they would prefer to do their own research, the top two reasons cited for not taking free advice are “I wouldn’t take advice if I didn’t trust the organisation” and “I wouldn’t take advice if I didn’t trust the adviser”.

Lack of transparency about fees and mis-selling of pension policies are two major culprits for driving mistrust.

More transparency around fees and better communication are key steps to building trust, she says. Without this, the actions of a few bad apples may tarnish the wider industry. “There are some first-class financial advisers who do a very good job, advising people with total probity,” says Colin Mayes, director of PR, UK and Ireland, at professional services firm Aon. “Unfortunately, there has needed to be a lot more written about people who aren’t so scrupulous.”

Complexity

Like many areas of financial services, pensions suffer from complexity and overuse of jargon. Complexity is a powerful force which has the potential to bore, daunt and confuse. It turns people away and makes ignorance seem like bliss.

The FT’s Cook points out that many people are “almost frightened of pensions…they shy away from finding out how they are doing because if they find out what the shortfall is, they will have to do something about it.”

A recent straw poll run by the FT’s Consumer Editor Claer Barrett on social media platform Instagram tells a similar story. Barrett asked followers to describe how they feel about pensions in one word. The results read like a thesaurus entry for the phrase ‘turned off’, with ‘confusion’, ‘lost’, ‘scared’, ‘frustrated’ and ‘terrified’ all featuring. The majority of savers are clearly daunted, confused or both.

Role Call

When it comes to building trust and improving engagement, various stakeholders have a role to play. By analysing the roles of the media, employers, regulators, the industry and the individual, our report seeks to unveil the steps necessary to change perceptions around pensions and restore public confidence.

1. Role of the media

The media clearly has a vital part to play in informing the public. Retirement is an issue which impacts everyone and, with 32 million people employed in the UK and 10 million over-65s, it stands to reason that pensions should receive significant press attention.

While the media often tends towards negative stories, Daley – a former Personal Finance Editor at The Independent – argues it is not responsible for the pension industry’s poor public image: “It’s the media’s job to report on things of interest; you can’t blame the media,” he says.

Nevertheless, it is an influential voice and certainly has a role to play in either reinforcing or changing perceptions.

“We’re talking about everyone’s long-term savings, but some newspapers tend to illustrate articles on pensions with pictures of wrinkly, old people,” says Hosking. This doesn’t help to position pensions as an issue younger people should be paying attention to, he admits.

In a sense no news would be good news. “If pensions did what they were supposed to do, there would be far less reason for them to make headlines,” argues Morrow.

There is no shortage of pensions news flow, either. Hosking notes that “even the most microscopic or esoteric changes n pensions legislation can prompt 20 or 30 comments”.

Perhaps, though, part of the problem is just that: the pensions industry is more comfortable speaking to itself, rather than its customers.

This narrow focus is reflected by the finding that only 15% of respondents in our survey said they consulted the media for all, most or some of their information about retirement planning and pensions.

In recent years digital platforms offering financial advice and guidance have mushroomed in popularity, as have consumer websites like Money Saving Expert and primetime programmes like ITV’s Money Show, fronted by MSE founder Martin Lewis. Indeed, Lewis himself was recently voted the most trusted person in the UK.

These channels provide valuable sources of information about retirement savings and serve to reinforce the media’s role in holding the pensions industry to account.

This, in conjunction with information from other stakeholders – employers, regulators and providers – helps people make informed decisions, and to do so with confidence.

2. Role of the employer

Of all the stakeholder groups, employers have the most frequent and direct access to, and interaction with, pension savers. This gives them the greatest opportunity to build trust, raise awareness and positively influence savings habits.

Companies are increasingly alive to the importance of workforce wellbeing issues. As a result, says Mayes, pensions is once again becoming an HR and ‘people’ issue: “This is a key moment because people will trust their employer much more than an outsider.”

Of course, much more needs to be done. According to Aon’s recent DC member survey, just 15% of respondents felt their employer offers a very good level of financial wellbeing support, while around one in three (30%) said their employer offered no support in this area. A further one in six (16%) did not know what support (if any) is available.

But the survey also found that employees increasingly want their employer to help them. “They don’t know what to do with their pension pot, or what options they have, so some of the onus is going back to the employer to give guidance,” says Mayes.

Hosking agrees employers should do more to communicate. “A few of the more paternalistic ones have held events like annual pensions clinics for their employees but most have missed a real opportunity to show they really care about staff financial wellbeing.”

For smaller organisations this can be more challenging, but employers must seize the opportunity provided by auto-enrolment and not view greater engagement as an administrative burden.

3. Role of regulators and policymakers

The message for policymakers and regulators from our conversations is that sometimes less is more. “Constant tinkering means that goalposts are moved by political whim,” says Fairer Finance’s Daley.

The glacial pace of movement in advancement of policy is a hurdle that must be overcome. It has been 16 years since the Pensions Commission which gave rise to the concept of auto-enrolment, but the policy was only enacted years later.

“The time horizon for pensions is decades, but everything about the financial industry keeps changing – from the names of pensions providers to government ministers, nothing stands still,” says Hosking.

Indeed, trade publication Professional Pensions recently reported there have been 15 pensions ministers since the role was created in 1998. For context, Chelsea – the football club renowned for the frequency with which it hires and fires its managers – has had 19 managerial changes in

that time. With a new figure taking the reins every year or so, inaction around policy enactment and delivery is inevitable. Continuity should not be underestimated in terms of its power to build trust, instil confidence and promote engagement.

Continuity aside, the FCA and TPR’s recent call for evidence on the pensions customer journey identifies three specific barriers to engagement: low understanding of pensions; difficulty in moving products or changing contributions easily; and inability to achieve a comprehensive view of pension saving. None of these barriers can be overcome without regulators and policymakers prioritising customer-centric reform.

4. Role of industry

If politicians and policymakers dither and delay, the same could also be said of the pensions industry itself. A good example of this procrastination is the much-vaunted and long-awaited pensions dashboard.

Hosking notes that the average worker will have 11 jobs during the course of their career, which with auto-enrolment, means an awful lot of pension pots to consolidate.

The dashboard would do just that but even the latest target rollout date of 2023 is under threat from a lack of clarity, according to the Society of Pension Professionals. It is a clear example of industry inertia, whereas action – and communication of such action – to make a dashboard work could be a powerful signal of industry intent to bring pensions into the modern age.

Similarly, our respondents noted the pensions industry’s frequent tendency to use scare tactics to get its message across. “There are way too many press releases pumped out saying ‘you’re not saving enough’ and it’s not very helpful,” says Hosking. “People would rather have jam today even if they might live until they’re 90.”

This problem persists to this day. In 2020, the Money and Pensions Service (MaPS) set out its UK Strategy for Financial Wellbeing which highlights improving understanding of pensions as a key part of boosting financial wellbeing. This is a 10-year plan, which reflects both the pace of movement in changing attitudes or behaviours, and the distance left to travel.

“You need a bit of both fearmongering and inspiring, but the vital thing is to turn the volume up,” says Daley. “Government and industry have to amplify the messages.”

Ultimately, the pensions industry has to take responsibility for driving a change in mindsets. Mayes shares an anecdote to illustrate the point. “Almost 20 years ago I saw a speaker tell an audience of HR directors that they face a generation of people who will get to the end of their working life and realise their pension pot is not big enough,” he says. “He left the stage to the sound of his own footsteps; the audience didn’t want to know.”

Much like the individuals that perennially put off getting their finances in order, industry figures must grasp the nettle and confront the issue head-on.

5. Role of the individual

Of course, at the heart of pension saving lies the individual. Their role has changed dramatically over the course of the past three decades, as investment risk has transferred to

employees with the demise of gold-plated final salary schemes and the introduction of auto- enrolment.

“The DC pensions that replaced final salary schemes were ‘sold’ to employees as being portable and the risks being passed over were not explained,” says the FT’s Cook. “More recently employers have moved to auto-enrolment for new employees, reducing even further the amount they pay into their pensions.”

The less generous DC schemes which now represent the norm fluctuate in value with the rise and fall of stock markets, meaning pension savers are far more exposed to the traditional risks associated with investing. For most, that means managing pensions and investments is something that will need to do be done throughout the working life-cycle and well into retirement beyond.

However, most people are ill-equipped to manage these investments – and their risks.

“The problem has been exacerbated in the past decade by an increasingly short-termist culture,” says Daley. “Things like ‘buy now, pay later’ and payday loans grate against the

goal of establishing long-term saving habits. Nowadays, people tend to borrow more and save less.”

In the absence of meaningful communication from employers and providers, individuals will need to take matters into their own hands. In this sense, a cultural shift is required. As the FT’s Barrett concludes: “All too often, it feels like the pensions world does not engage with us. But to get the best bang for our buck, we also need to ask more questions and be more demanding of our providers.”

COVID-19: A chance to reset?

The pandemic has caused many to re-consider their priorities. In the short-term, protecting lives and livelihoods has been paramount but significant behavioural shifts have also been observed. For example, lockdowns have led to a huge build-up in excess savings – reaching £170 billion in April 2021, according to analysts at investment bank Morgan Stanley.

But it’s a mixed picture (see Chart C). The Financial Conduct Authority recently found that the pandemic had left over a quarter of UK adults with low financial resilience. Moreover, 27.7 million people – roughly half of UK adults – now show characteristics of potential vulnerability through low financial knowledge or low financial resilience, poor health or life event affecting their financial wellbeing, or a combination. That’s an increase of 3.7 million since the pandemic began.

And as Chart C shows, higher income households and retirees are more likely to have increased savings during the pandemic, potentially widening existing wealth inequalities.

Our conversations with industry participants suggest it is too early to tell if the pandemic will result in a change of attitudes towards pensions longer-term.

“Previous generations emerged into the post-war period where the world had been shaken and people realised that having some form of long-term protection was a valuable safety net,” says Daley. However, he is unconvinced that the pandemic will ‘inspire’ young people in the same way: “The memories from that time are gone. For younger generations, it’s something from the history books.”

Short-term behaviour certainly still dominates. The recent bout of stock market speculation in GameStop shares and the surge in cryptocurrency trading – often driven by novice day-traders – suggest people will still invest in things they don’t understand in the hope of making a fast buck.

Mayes is sympathetic to this lack of longer-term focus. “You can’t expect people to worry about what they’re going to be doing at 72 if they haven’t got any money now, at 27.”

For those who may have taken stock of their finances during Covid-19 and, importantly, can afford to think longer-term (see Chart C), this is a moment that should be capitalised upon. As the FT’s Barrett says in her April 2021 column, mindsets may be shifting: “A year ago I would have been inclined to believe the argument that many young people were uninterested in pensions. However, the surging numbers who have started investing during the pandemic has changed my mind”. In this sense, one positive legacy of the pandemic might be that it serves as a moment of reset.

Fixing The Problem

Our interviews with industry players highlight a number of recurring themes and issues that communicators need to address to improve engagement and trust in the pensions sector. They include:

Financial literacy – spell it out clearly

Financial education and literacy are vital if the pension industry’s PR problem is to be addressed. From the evidence we’ve seen and heard in our research, it is clear that while progress has been made, there is still a long way to go in building trust and confidence.

An April 2021 study from investment app Freetrade shows that half of UK individuals do not know what the term ‘ISA’ stands for, while retirement was identified as the area of personal finance that people most struggle to understand. Further, a vast majority (90%) of Britons said they lacked confidence in managing their retirement money. Dan Lane, senior analyst at Freetrade, says this should be causing “alarm bells” and points to longevity trends to highlight that this issue risks getting worse: “We really aren’t prepared for a sizable portion of our lives,” he observes.

But the ‘wake-up call’ approach only goes so far in galvanising people into action. That’s why more financial literacy and education are needed to help dispel myths and bring expectations more into line with reality.

Cook would like to see greater effort dedicated to hosting and promoting safe forums for discussion of such topics, to remove the stigma of inaccessibility and mystique that can surround financial services in general.

“There needs to be better education. Years ago, employers would provide pension seminars to help people work out what they need to retire and to guide them,” says Cook. “Now they often feel alone.”

Although financial literacy has been part of the curriculum since 2014, it typically forms a module as part of a broader subject, rather than receiving standalone treatment. The good news is that there is seemingly an appetite for understanding personal finance among younger people, even if pensions isn’t top of that agenda. London Institute of Banking and Finance research finds that 8 in 10 students want to learn more about money during school, reinforced by Save the Student’s 2020 survey, in which three quarters of students said they did not get enough financial education in the classroom.

Literacy can start in the classroom, but the industry can learn some of the same lessons: the quickest and easiest way to improve understanding is to remove jargon – and there are no costs attached to doing so.

Another opportunity for the industry to improve engagement levels with younger people and encourage them to invest for the future is Child Trust Funds. According to HMRC, more than six million people born after September 2002 will be eligible to redeem their money or continue to invest tax-free via Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs) when they turn 18. However, awareness of the scheme is low and billions languish in accounts, effectively unclaimed. So far then, not the industry’s finest hour.

Relevancy – partner pensions and purpose

Our interviews found that employees are looking for their employers to make the first move when it comes to communicating about pensions. A once-yearly update on a benefits package is not enough – the pensions conversation should be part of a continuous dialogue.

The rationale for greater time and resource investment here is not just financial. Increasingly, employees expect the companies they work for to take a stand on issues and to have a purpose above and beyond maximising profits for shareholders.

The same ‘stakeholder capitalism’ trend is also evident in the investment industry. The increasing popularity of funds specialising in corporate social responsibility, especially

among young people, is more than just a marketing opportunity. It is also a chance for communicators to better explain the role of pension funds in modern society, and how savers can actually make a difference by choosing the funds they invest in.

This needs to be done in an authentic way. Most pensions providers need to do more to get the message across to individuals who have an appetite for changing the world that pensions are an important tool for driving societal change.

Auto-enrolment – still all to play for

According to the ONS, 78% of UK employees now have a workplace pension, compared to less than 50% before auto-enrolment was introduced in 2012.

Auto-enrolment really matters from a pensions communications perspective because it affects so many people. More than 10 million people now pay into a workplace pension. Hosking points out that anyone who is invested in an auto-enrolment scheme should have had “a fantastic run” recently given the strong returns delivered by stock markets.

“It’s a good example of intervention working,” adds Morrow.

However, auto-enrolment’s shortcomings are also evident. “Involvement has increased, but not engagement,” says Daley. “Auto-enrolment does nudge people, but it puts you in a passive position as a consumer.”

Mayes agrees that auto-enrolment must be viewed as only a start. “It is a good thing, but the levels involved are not sufficient, so part of the issue is around communication, which schemes are well aware of.”

So far opt-out rates have been far lower than expected but these are no grounds for complacency. As noted, the main flaw of auto-enrolment is that current minimum contribution

levels are nowhere near enough to provide anything like a comfortable retirement, but this is not very well explained.

The Investing and Saving Alliance (TISA) is among the voices calling for minimum contributions to increase.

It’s hard to disagree with Renny Biggins, Head of Retirement at TISA, when he says it is the collective responsibility of government and industry to ensure auto-enrolment remains a success: “We believe an increase in minimum contribution rates to 12% of salary would just about achieve a balance between an inertia approach and the opportunity to achieve enhanced outcomes through engagement.”

In technology we trust?

It may be tempting to think that by making access to financial information easier, technology can overcome at least some of the communications challenges we have outlined. Fintech in general, and the rise of first open banking and now open finance in particular, offer customers convenience and easy access to data like never before.

But our interviews suggest the onus is still too much on the individual to be proactive whereas customers look to the industry or their employer to take the lead in communicating with them. In other words, fintech is a useful tool in the communications armoury, but it is not a silver bullet. There is a danger therefore in relying on technology alone to solve everything. It simply can’t be expected to do all the heavy-lifting.

Take the pensions dashboard, which is very much a creature of the open finance revolution and where expectations may be unrealistically high. “I’d rather get pensions products right and fit-for-purpose than focus on an expensive dashboard which might suit a small number of people but would be ineffective if it isn’t comprehensive,” argues Morrow.

Technology certainly has a key role to play in designing those products. Morrow believes there is an opportunity to create something “radical and fit for the future” which reflects modern life and requirements: “There has been so much change in society and human development. The single-job career reflected simpler times. It doesn’t make sense that pensions haven’t changed.”

Structural issues present barriers to engagement, and technology will certainly not eradicate them all. But getting a holistic view of pension savings is one such barrier which technology can help to overcome. Saving over a long time period means it is hard to keep track of how much is being saved, where and with whom. If the pensions dashboard can provide an accurate and comprehensive one-stop shop for consumers to view their pensions, it would go a long way to removing this barrier. Once again, the industry must ensure it sets appropriate goals and expectations for technological ‘solutions’ like the dashboard and, crucially, communicates these expectations effectively.

Conclusion

Our report began by stating that pensions have a PR problem. The message that we are not saving enough for retirement is not cutting through.

Our research also found that the media, while still an important source of information for some, is not the most important – or even the most trusted.

For communicators, our findings present considerable challenges. More people than ever feel they are having to stand on their own two feet when it comes to retirement planning. But too many of them lack the knowledge or confidence to make informed decisions or to seek financial advice – even if they could afford it. The information savers receive must be simplified, and the timing of when they receive it must be more uniform. Initial steps like the PLSA’s jargon-busting guidance must be capitalised upon, while the introduction of simpler annual benefit statements is also overdue. Simplicity must be championed and cherished.

Providers and those in the advisory community should embrace and foster an openness to engage with personal finance journalists on a more ‘human’ level rather than only focusing on technical subject matter. The media is a key vehicle through which trust and understanding – of both an organisation’s products or services but also of pensions issues more broadly – can be built.

Read about pensions today, however, and it feels like a specialist subject. But pensions are not a minority sport. Their lack of mass appeal shouldn’t add up. Communications and marketing must come together and harness the influencing behaviour deployed so expertly by technology and consumer brands. ‘Swipe right’ for pensions may seem far-fetched, but attempts must be made to tap into consumption preferences and social movements. Aligning preference and purpose through awareness-raising is what will drive change. Storytelling is vital.

Lack of engagement stems from a number of factors, including:

• failure to acknowledge the importance of an issue

• perception that an issue is inaccessible, complicated, boring

• scepticism or mistrust in individuals and/or institutions

By the same token, driving engagement depends on:

• bringing into greater focus why an issue matters

• making the issue more engaging by raising awareness and profile

• addressing or allaying the concerns of critics and sceptics

In this respect the communications challenges facing the pension industry are by no means exceptional or different from those faced by other industries. It’s just that they matter

more because the stakes are so much higher. For everyone.

How can we help?

Get in touch with our team