The media’s role in building momentum for onshore wind

August 31, 2023

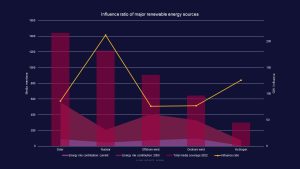

Last month, to coincide with UK Net Zero Week, Infinite Global released Plugged In – an analysis of over four years of UK media reporting data for the major renewable energy sources, including onshore wind, identifying which had the largest volume of media coverage and comparing this to the planned contribution of each one to the country’s energy mix by 2050, as per the current Government targets.

Based on this comparison we assigned each technology an ‘Influence ratio’, measuring how far they are currently performing above or below expectations in terms of media profile. From this empirical basis we can begin to identify where the communications challenges lie for each renewable energy source, how they might affect current and future levels of deployment, and what the potential solutions could be.

We will now look at some of the different technologies in turn to explore these questions in more detail. We begin here with the joint-lowest scorer: onshore wind (influence ratio = 77).

Onshore Wind – Challenges

Of all the renewable technologies that are expected to play a role in the UK’s transition to net zero, it is hardest to gauge accurately the level of influence commanded by onshore wind, and whether it is commensurate with its potential as a sustainable energy source.

This is partly because onshore wind has been subject to an unusual degree of political uncertainty and policy fluctuations in recent years (acutely so following Liz Truss’ mini-Budget and its near-total reversal under Rishi Sunak).

Unlike other renewable energy sources (including its sibling, offshore wind), the Government has not directly committed (yet) to specific onshore capacity targets for 2035 or 2050 (for the influence ratio calculation we used the projected capacity level modelled by the Climate Change Committee in the 6th Carbon Budget).

However, what is certain is that onshore wind is currently a significant contributor to the UK’s renewable energy production, with over 14 GW of capacity currently deployed (representing approximately one quarter of installed renewable capacity). Plus, the UK has the abundant wind resources to potentially deploy capacity to generate an estimated 29-96 GW onshore at relatively low cost.

Why then might onshore wind have received limited media visibility to date compared to the other renewable energy sources? Given it has been the subject of multiple high-profile policy reversals by central Government in the past year alone, anyone would be forgiven for assuming otherwise.

Here are six factors we’ve identified that may be contributing to the current landscape:

- The challenging art of political compromise. It has been reflected on in the media that there is little consensus among MPs on the right policy approach to onshore wind. Political disagreement can raise the profile of an issue in the media, however it can also limit its influence if the perception is one of impractical barriers to striking a compromise, or that such a compromise may ultimately be ineffectual. The narrative follows that these kinds of political footballs are invariably kicked into the long grass. There is some evidence of this narrative surrounding the government’s attempts to reform the 2015 planning rules that amount to a de facto ban on new onshore wind developments. The Government has consulted on proposed reforms to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) as part of the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill which it promises will hand more decision-making power on new onshore wind developments to local communities. However, industry bodies such as RenewableUK have publicly criticised the language in the proposals as being (as yet) ambiguous and it is unclear how the rules would work in practice, particularly for demonstrating local community support and that planning impacts identified by local residents have been “sufficiently addressed”. Various industry commentators have expressed doubt in the media that the approach proposed will yield a workable compromise that can facilitate greater deployment rates (see reported here and here for example). Conservative MPs themselves remain divided on the right approach to take. In July a group of Tory backbenchers including Liz Truss and Sir Alok Sharma tabled an amendment to the Energy Bill to remove the relevant clause – Footnote 54 – from the NPPF entirely, as opposed to reforming it as per the Government’s proposals. These circumstances naturally redirect media focus away from the technology itself and its application to the net zero transition, and towards the political landscape. It is notable the media did pay attention to Rishi Sunak’s decision last month to delay the decision on removing the ban until the Autumn.

- Historic perception of local community opposition. Related to the point above, the political (and to some extent media) debate has historically associated onshore wind developments with heightened local opposition (so-called Nimbyism), particularly among demographics and in regions viewed as strategically important on an electoral level for the current Government. As we will discuss below, public opinion is changing and the media is taking note. However, perceived local opposition is still being interpreted in the press as a drain on the current political will to meaningfully reform the planning rules, further affecting the influence conferred on onshore wind in the media, essentially for reasons of perceived feasibility.

- National significance. In terms of national media specifically, the general nature and scale of individual onshore wind developments mean they can be less conducive to high-profile media reporting on a project-by-project basis, relative to more large-scale, nationally-significant energy infrastructure projects, which are often tied up with wider geopolitical questions that are the natural milieu of the mainstream media. A good comparison to draw is with nuclear (see detailed coverage of Hinkley Point C for example), the highest scorer on the influence ratio due to its large media profile despite a lower planned capacity than the likes of solar and offshore wind.

- Financial scale. Similar to the above point, the general scale of onshore wind projects makes them less individually significant from a financial or investment perspective, and therefore less likely to be reported prominently on a project-by-project basis by the business and financial press. For a sense of relative scale, look at the renewable projects that received financial support from the Government in the latest Allocation Round of the Contracts for Difference. A quick analysis of the latest published results shows that the average size of the 10 successful onshore wind projects was just under 90MW. Meanwhile the average size of the five successful offshore wind projects was just under 1,400MW. The disparity is considerable and will clearly extend to financial aspects such as capital expenditure requirements, operational expenditure, investor profile, etc.It is understandable that offshore wind as a sub-sector currently commands considerably more influence in the media than onshore, at least at the individual project level (see for example the detailed reporting of Swedish energy group Vattenfall’s decision to halt development at the Norfolk Boreas offshore wind project – total investment approx. £10-11billion). Admittedly, it’s a similar picture for solar projects as for onshore wind. Both are comparatively small and low cost on a project level. Nevertheless, solar received the highest number of media mentions of any technology in our study. This is probably because of the significant proportion of solar installations delivered at the domestic, residential level (approximately 27% of the UK’s total solar capacity and contributing 73% of the added solar capacity in 2022, according to one report). This increases the perceived relevance for the mainstream media audience who are more individually empowered to deliver new solar installations themselves.Admittedly, this is also partly true for domestic wind turbines, but the land and other requirements do perhaps make them less practical for the average household. Solar deployment has also been the subject of various Government policy initiatives which likely further boosted its influence in the press (this will be discussed at greater length in a subsequent article on solar).

- Variable versus controllable energy generation. While there is general agreement that onshore and offshore wind, and solar energy, have important roles to play in the UK’s transition to net zero energy production, they have a fundamental disadvantage compared to other energy sources in that they are variable or intermittent in energy output depending on uncontrollable factors. Namely, weather conditions. They are therefore not as dependable as the likes of nuclear or fossil fuels and so cannot, in current form, be relied upon to meet the UK’s fluctuating energy usage demand. Variable renewable energy necessitates the development of large-scale energy storage, through the use of batteries or hydrogen (see an example of the former reported here) which presents more of a technological and logistical challenge to develop and deploy. In other words, onshore wind is often not considered a solution in itself and ultimately directs industry and media attention towards other technologies. It also overrides other perceived benefits of onshore wind, such as its relatively low cost, since in practice it necessitates additional expenditure on other complex energy infrastructure.

- Novelty and innovation. Onshore wind is a tried and tested technology that has been deployed in the UK for energy production since the nineteenth century. The first modern commercial wind farm was deployed in the UK in 1991. This may be affecting the perceptions of the media and others of the innovativeness and novelty of new onshore wind projects.

Impact

The media has a considerable influence on the shape and sway of public opinion and sentiment. This is why, in Plugged In, we suggested that a comparative lack of media penetration of onshore wind may be a contributor to some of the issues highlighted as holding back its expansion. This almost certainly includes the real and perceived local community opposition to new developments. However, it also extends to other areas such as project finance and investment, since we know that the way the media delivers information (or doesn’t deliver information) to investors and markets can have a considerable influence on financial outcomes, e.g. for new energy projects. Arguably, in the context of climate change and the wider ESG agenda, the influence of media reporting on investment decisions may well be heightened given the public debate and scrutiny of things like greenwashing which pose a severe reputational and legal risk to investors and other stakeholders.

It is however hard to fully assess the impact of suboptimal media engagement on renewable energy deployment, partly because the real impact is that of missed opportunities.

Solutions and Opportunities

Each of the communications challenges facing onshore wind in the media and elsewhere is based to a greater or lesser extent on perceptions, some more accurate than others. The reality however is that the landscape for onshore wind is shifting rapidly, largely in its favour. The nature of the media is not only that it reflects prevailing understanding and opinion on a topic, but it also informs and influences it. The challenges listed above can therefore be seen as opportunities for renewable energy companies looking to alter the narrative, tell the story of onshore wind, and use the media to bring more potential stakeholders onside.

Here are a few ways to think about changing the narrative:

- Whatever the final outcome of the current or future attempts to reform the planning system for new onshore wind developments, demonstrating local community support and addressing local resident concerns is a complex communication and stakeholder relations challenge, one in which the media (particularly local media) will be a crucial player. Therein lies significant opportunities for developers, local authorities, and others who can succeed in engaging with the media constructively to raise awareness and communicate the benefits of local onshore wind projects to local residents and businesses. Not only can this help support the planning process, but it can also help with other legal and commercial challenges to new onshore wind developments, such as identifying and engaging potential parties for things like power purchase agreements or PPAs (a recent example reported here) which can aid the financial viability of new developments. In other words, the media does not just report the solutions that are helping overcome barriers to new onshore wind, it can be made part of the solution.

- Regardless of how it has previously been perceived and depicted, evidence suggests that onshore wind increasingly enjoys broad public support – particularly in the context of worsening fears around climate change (at the time of writing we’ve just emerged from Europe’s hottest summer on record, causing widespread fires and disruption in the southern countries), as well as the cost of living crisis and specifically recent spikes in the cost of energy from fossil fuels. The likes of onshore wind represent a low cost and low carbon alternative. This is something that politicians, the media, and the public are becoming more and more alive to.

- The possibilities of how an onshore wind project can be designed and how it can function are evolving rapidly. The industry and technology are adapting, for instance, to the challenges of intermittent wind power generation, by developing new hybrid projects (see example reported here) that incorporate both onshore wind (often combined with solar) and energy storage methods in both on-grid and off-grid solutions. Microgrids are being pioneered for renewables such as wind power that not only mitigate the issues around severe delays to grid connections but also ensure the energy produced benefits the local area and community directly, helping to meet one of the key criteria for new developments. These kinds of projects are more complex, more innovative (enhancing the UK’s credentials as a climate-tech leader), and require higher levels of investment to deliver, simultaneously adding to their relevance for mainstream and financial media audiences.

Conclusion

The clear direction of travel is towards ever-greater emphasis on communication as a key facilitator of new onshore wind development in the UK. It is important that any strategy aimed at successfully delivering a new onshore wind project includes detailed consideration of the media landscape and where the project sits in it – and the potential for positive reporting. The media can act as either a barrier to or an enabler of public awareness and support for renewable energy developments. The determining factor will be the level and style of engagement, and fundamentally whether the project has the right story to tell: locally focused and nationally and globally conscious.

Harrison Howard is a Senior Account Manager at Infinite Global

How can we help?

Get in touch with our team